Matisse: The Red Studio – a painting on paintings stuns at MoMA

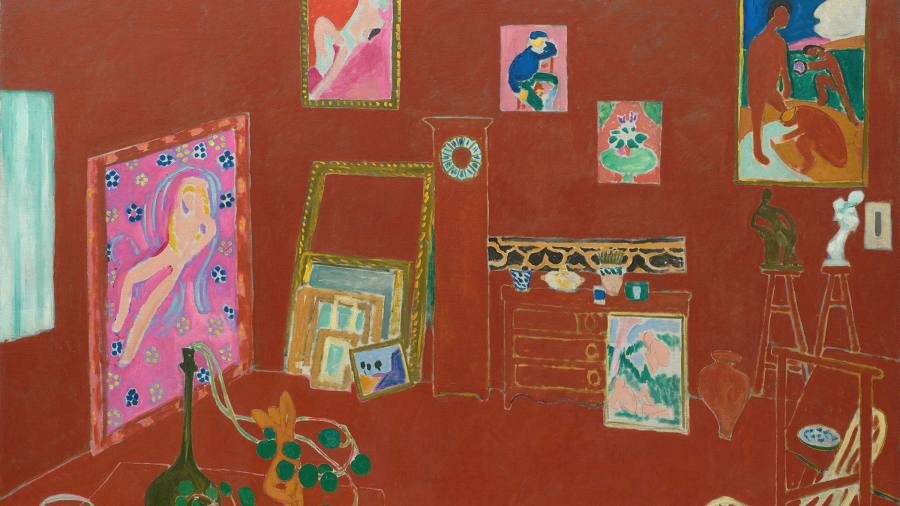

More than a century has passed since Henri Matisse created “The Red Studio,” a painting of a room full of paintings, and I’ve seen it countless times at MoMA. Yet he did not give up the ability to shake and exalt. Its radicalism endures. This is where Matisse found the ideal marriage between large blocks of color and nervous patterns, between space and the paper-thin surface.

Modern art took a turn the day he signed this opus, and Matisse himself too. MoMA has built an enchanting little show around this unique masterpiece, bringing together “The Red Studio” with 10 of the 11 Matisse paintings and sculptures it depicts. This first gallery details how Matisse treated his sanctuary as a kind of self-portrait, each object representing a piece of his past, his tastes or his aspirations. A second section traces the work’s journey after it left Matisse’s hands, spending decades in the desert before settling as one of the museum’s most august treasures.

In 1911, the Russian textile magnate and faithful patron of Matisse, Sergei Chtchoukine, invited him to decorate a small room in his palace in Moscow. The first part was a photo of the artist’s studio in Issy-les-Moulineaux, alluringly decked out in shades of pink. The soil is a rich salmon; the walls have a mauve hue, dotted with green and gold flecks. Matisse took some liberties with verisimilitude – the actual walls were white – but kept the composition grounded in physical reality. A yellow rug recedes diagonally inside the stage, tables line the mid-plane, and vertical wooden panels line the far wall, where a window opens to a garden beyond.

Later that year he followed up with “The Red Studio”, and this time he completely got rid of the illusionist space. We can no longer tell the ceiling from the wall or the back from the front. Everything is suspended in a single plane, awash in a sea of Venetian red. The gaze wanders, rests here and there on floating canvases. Ivy shoots out of a dark green vase that rests ostensibly on a table but also appears to levitate.

Detail of ‘The Red Studio’ showing, in the centre, the ‘Young Sailor II’ (1906) © Succession H Matisse/ARS

The original ‘Young Sailor II’ © Succession H Matisse/ARS

Matisse was interested in color without mass, in luminescence without gravity. In 1912, he wrote to Chtchoukine that he had made a study in “blues, pinks, yellows and other greens representing the paintings and other objects placed in my studio”. To make his point better understood, he accompanies this note with a small watercolor study. Shchukin quickly dismissed it.

He was not alone. No one had yet imagined a scene so detached from the visible world. And yet, it wasn’t so much his technique or abstraction that confused viewers as his aura of deceptive simplicity. A reviewer who saw “The Red Studio” at the 1913 Armory Show in New York reported that Matisse “throws figures and furniture onto his canvas with precisely the lavish impartiality and reckless draughtsmanship of a child”. A less censored way of saying this might be that it yearns for the child’s ability to slip between reality and imagination, or that it merges fantasy, fun, melancholy and exhilaration. Instead of windows to nature, we get images that open to perspectives of the mind.

The MoMA exhibition allows us to penetrate this fervent brain, to see Matisse’s works as they were, all together and life-size. Bringing together the six paintings, three sculptures and a ceramic plate was a Herculean feat of detection by two teams of curators, led by Ann Temkin at MoMA and Dorthe Aagesen at SMK, the National Gallery of Denmark. (They even found a tiny headless terracotta figurine that had been hidden among the possessions of Matisse’s son, Jean.)

Detail of ‘L’Atelier Rouge’ showing ‘Corse: Le Vieux Moulin’ (1898) © Succession H Matisse/ARS

‘Corsica: The Old Mill’ © Rheinisches Bildarchiv

The resulting mini-retrospective-within-a-show traces Matisse’s growth and desires as they unfolded in 1911. “La Corse, le vieux moulin” (1898) evokes the mood of his honeymoon in Ajaccio, this first close encounter with the Mediterranean sun and the revelation of the glowing sea. Her amazing gift for color comes through in puddles of pink, purple and aquamarine. Stone walls vaporize in feathery strokes.

Seven years later, he realized his Arcadian vision “Bonheur de vivre”, where the landscape merges with sex. If the work itself is absent, its idyllic languor permeates the gallery. In “Le luxe (II)” (1907), three nudes frolic at the edge of blue-green waters, with breast-shaped hills beyond. Bodies are opaque, flesh-colored forms; the sunny Eden beyond is even more bare. The light comes from nowhere and covers everything. Time is suspended.

This pensive joy expresses an ambition he had not yet realized: painting as a kind of sublime therapy. “What I dream of is an art of balance, purity and serenity, devoid of disturbing or depressing subject matter, an art that could suit any mental worker, businessman as to the businessman”. letters, for example, a soothing and calming influence on the mind, something like a good armchair that provides relaxation from physical fatigue.

‘Le Luxe II’ (1907-08) above two sculptures in a detail of ‘The Red Studio’ © Succession H Matisse/ARS

‘Luxury II’ © Succession H Matisse/ARS

In the years following “The Red Studio”, this urge drove him to even greater extremes of flatness and abstraction. The exhibition includes “Nasturtiums with the painting ‘Dance’ (I)” (1912), in which a table and a vase of flowers straddle two- and three-dimensional worlds. A table leg reaches the stage which leans against the wall, the other two sit on the inclined floor. Space and representation have merged.

And what about the artist’s desire to soothe the breasts of tired writers and financiers? He finally got that wish too. In the second part of the show, “The Red Studio” languished out of sight for 15 years, then a nightclub owner bought it for the Gargoyle Club in London. There, an elite roster of plutocrats and bohemians sought solace in each other’s company, in the plentiful booze, cheerful music and glowing hues of Matisse, endlessly reflected in the mirrored walls of the ballroom. Eventually the fun died down and the work found its way to MoMA.

Towards the end of his life, Matisse returned to his old preoccupations. In his last completed oil, “Large Red Interior” (1948), paintings, flowers, furniture and pets are all pressed against the same vermilion plane, as if to reiterate that the real world he inhabited was not a place depth and shadows. but a brilliant roll of offered delights.

As of September 10, moma.org

To follow @ftweekend on Twitter to hear our latest stories first

Comments are closed.