“Painting by numbers” by Diana Seave Greenwald | Culture & Leisure

“Painting by Numbers, Data-Driven Histories of Nineteenth-Century Art†makes you feel like you’re about to learn how to apply color to a line art with subdivided digital spaces, indicating where to insert the tints numbered – this is not the case. This volume takes a look at artists of the past who turned to portraiture, landscape and genre, but why? As a painter, I think it’s important to understand where you stand in the art’s timeline, even if the gravel is slippery at times and your foot becomes unstable. Did artists from another era choose categories based on their whims or were they influenced by the era and environment in which they lived? Greenwald, art historian and economist, has researched and presented graphics, which can be intimidating. Don’t worry, his story is very clear. I recommend reading the text first and then going back to the data. Four tables in this book provide a visual explanation.

Les Glaneuses, 1857, by Jean-François Millet

‘Les glaneuses’, 1857, by Jean-François Millet, who wrote, “Paris, black, muddy, smoky”, is an example of a 19th century French painting, free from the grime and poverty of urban Paris (Greenwald 52). The Industrial Revolution gave artists the railroad to work in the countryside and easily network with their colleagues and metropolitan merchants. While this image shows pristine horizons, it also depicts haggard peasant women picking up post-harvest leftovers for their personal survival. Artists like Millet have portrayed the grim realities of modern farming communities, disturbing a thriving urban audience, which needed to become real (Greenwald 55, 82). Agriculture and mechanized factories not only overworked the lower classes, but early technologies left communities in abject poverty that some with age-old skills could not assimilate. The ambiguities of the modern world were visibly manifested thanks to Millet.

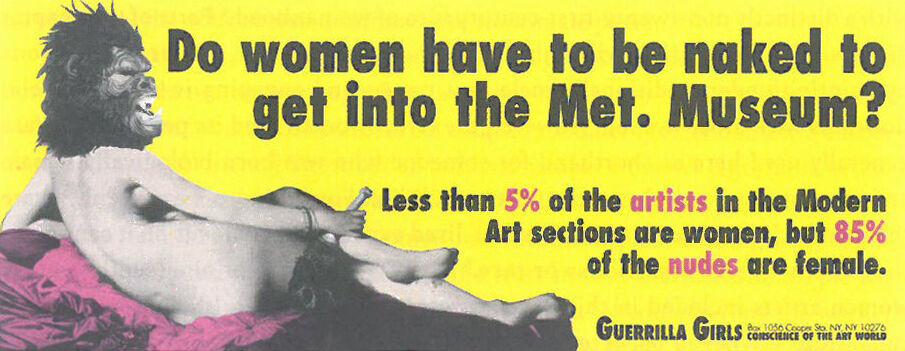

Guerrilla Girls, 1989

“Do women have to be naked to enter the Met. Museum ? Less than 5% of the artists in the Modern sections are women, but 85% of the nudes are women â€, 1989, is a poster for Guerilla Girls (Greenwald 85). The inclusion of this coin may confuse readers, as it does not date from the 18th or 19th century. Yet it is a reminder that today’s women in the art world still lag behind their male counterparts. In addition to being penalized for being a woman, maintaining a household, raising children, taking a second job and accumulating less money, women artists continue to derail. Traditionally, women tended to make smaller works, using pencils and watercolors, which could easily be picked up / cleaned up between other pressing responsibilities.

Some affluent women like Mary Cassatt found the European aesthetic atmosphere more welcoming. There was a colony of American female sculptors in Rome (Greenwald 102). Upon returning home, the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts began admitting women in 1844, but renting a studio was considered inappropriate. Women were excluded from art clubs reserved for men; in 1866, the Women’s National Art Association opened in Philadelphia (Greenwald 87, 88, 92, 93 101). Women continue to lack representation of merchants, which is why they still gravitate towards art cooperatives and show in cafes.

Fruits of Temptation, 1857, by Lilly Martin Spencer

‘Fruits of Temptation’, 1857, by Lilly Martin Spencer, is a genre painting, showing domesticity, although staged. Spencer was raised by progressive English parents who immigrated to Ohio. In 1844, she moved to New Jersey with her Irish husband, a tailor by trade, who became her shop assistant, helping to raise 13 children – 7 of whom survived to adulthood (Greenwald 103 104) . Highly unusual for being the breadwinner, Spencer became the most famous American artist of the mid-19th century, but felt underpaid. She wrote: “A progressive family life could nurture her professional ambition and facilitate her career, but did not protect her from the heavy time demands and professional repercussions of motherhood (Greenwald 104, 105)”. Spencer used his family as the subject, while his male contemporaries had more choices in rendering what was in vogue: patrician portraits and landscapes. Some would argue that Spencer was not the most famous female painter of her time, which could explain why so many works have been lost.

The Family of Sir William Young, 1767-69, by Johannes Zoffany

‘The Family of Sir William Young’, 1767-1769, by Johannes Zoffany, shows a prosperous English family on their estate. Their elegant brocades, pets and healthy children, sit under an ornamental tree adjacent to the wide stone staircase, the centerpiece of a stately home. Young was the son of a Caribbean doctor / planter. The family acquires wealth which allows entry into the British aristocracy (Greenwald 150). In the background, a black male figure, servant and trope of colonial conquests, smiles artificially, stabilizing those who ride horses. Greenwald concludes that painting the Empire was much less popular than making the homeland – “the green and pleasant land of England”, even though Britain, until World War I, controlled a quarter of the land. terrestrial world (Greenwald 115 116). According to Beth Fowkes Tobin, when Empire was sometimes depicted, the paintings “perform ideological works, in part, by depicting imperialism in such a way that the appropriation of land, resources, labor, and culture takes place. transforms into something aesthetic and morally satisfying (Greenwald 121,122). A few artists have succeeded in painting the details of Empire. Egypt and India, given their economic importance, were the most represented colonial spaces (Greenwald 130,131). An excuse for not painting the Empire was that it cost artists too much to travel to remote places deemed wild (Greenwald 127). With acclaim from art critic John Ruskin and painter Thomas Gainsborough, “British artists engage in what they can directly observe and the depiction of English landscapes has indeed become a point of national pride (Greenwald 129). ”

At the end of “Painting by Numbers”, Greenwald decides that 18th and 19th century institutions like the Royal Academy of Great Britain were justified in not showing the cruel realities of what was going on regularly in the colonies (Greenwald 151) . While it is true that British art buyers invested in and profited from colonial trade, as did dealers and institutions, they were all cowardly wimps, which Greenwald should have recognized. “Painting by Numbers†was released in 2021 after “Black Lives Matter†and the “Me-Too Movement†which forced museums and universities to reconsider what and how they show art, as well as who is funding the process. Nonetheless, this book contains poignant historical information for painters, especially women artists, who strive to paint the avant-garde, in the hope of showing in fair places. Some artists continue to be limited by money, travel, studio space, art material, genre, and therefore can only render backyard subjects.

Mini detective: “Painting by Numbers†by Diana Seave Greenwald is available on Amazon. Thanks – Jodi Price, Princeton University Press, for providing this book.

Jean Bundy is a writer / painter living in Anchorage and sits on the board of directors of IAIS-International.